As many (many) hot takes in various media outlets have proclaimed: adaptations are all the rage. Of course, adaptations have been around since the earliest days of moving pictures—and have always varied wildly in quality and success. For every Lord of the Rings and Game of Thrones, there’s a Legend of Earthsea or a Queen of the Damned. And even the ones considered successful often have their fair share of unsatisfied fans. What is it about transforming a written work into a film (or miniseries, television show, etc.) that gets us so excited (or so worried)? It’s easy to guess why studios love adapting; having an existing, successful script and built-in audience is certainly an advantage. Considering how often hardcore fans are disappointed in the big-screen iteration of their beloved source material—and casual viewers couldn’t care less—I often wonder what keeps bringing us back for more. Is it simply curiosity, the tantalizing prospect of seeing what we’ve only imagined?

What kind of magic do you need to make a good adaptation? What even is a “good” adaptation? Is it a faithful reproduction of the source? Does it use the material as a springboard to create something different? Is it a blueprint, or is it an outline? When is a novel/story/comic the complete basis of a film or TV adaptation, and when is it just inspiration? Does it matter when you experience the original vs. the adapted version? I wish I had the space or the time to dive into these questions with the depth they deserve. For now, however, I’m hoping to scratch the surface a bit with a rather specific test case.

Not so very long ago, I was what I like to call an “adaptation purist.” You know the type: the nit-pickiest, killjoy-iest of fans, the ones that can never accept deviations from the beloved source material and have to talk about it to everyone that mentions the movie. Loudly. And over the years, no film has triggered my fangirl ire quite like Practical Magic.

The book never really had an organized fandom, per se, though it was a bestseller when it came out in 1995 and the author, Alice Hoffman, was fairly well-known among a certain set of readers. I didn’t know much about it when I first encountered it by chance at the library when I was probably around 13 or 14, back when I was still picking most of my reading material at random from the options the nice librarians had set face-out on the shelves. Practical Magic isn’t a perfect book, but I found it at the perfect time in my life and it hits all of the right buttons for a comfort read, one I could return to again and again. I’ve read it at least a dozen times and can recite entire passages from memory at this point.

I’ve probably seen the movie Practical Magic almost as many times since it first made its VHS debut in 1998. This is actually rather odd, considering that until very recently I didn’t particularly like the film. It takes a deeply interior work about women’s lives and family dynamics and boils it down to a thin plotline about romance and poorly-planned necromancy. The music and tone are all over the place. Moreover, two of the book’s most interesting characters are aged down and clipped almost completely out of the story. In spite of this, and in dire need of witchy watching for my favorite holiday, I decided to re-watch the movie around Halloween last year and, for maybe the first time, I actually enjoyed it. I had been growing more and more mellow about it over the years, but this time I genuinely had fun. Maybe I was helped along by the twentieth anniversary appreciation pieces I had read around the same time, but I think it may have been something else…

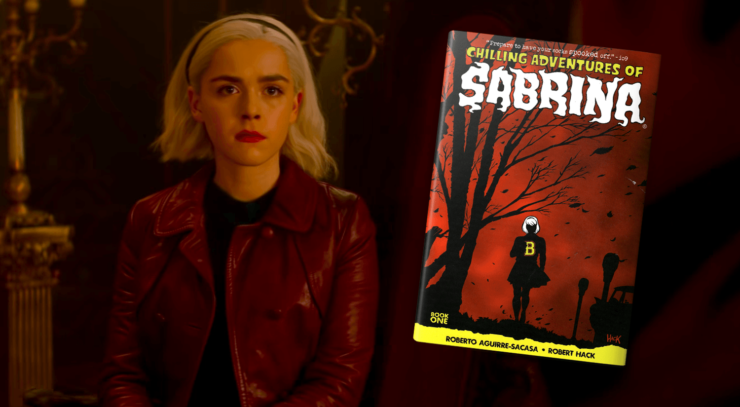

Another witchy adaptation, the first installment of The Chilling Adventures of Sabrina, was released on Netflix around last Halloween as well. Usually, being an “adaptation purist” also means that you simply MUST ALWAYS read the source material before you see a film or TV adaptation. However, I was too excited for Sabrina (and too wary of being spoiled by the internet) to wait, so I binged the show over a few days and resolved to give the comics it was based on a read soon after. The show was great—flawed and uneven in places, but a lot of fun. A week or so later I read the first 7 or 8 issues of the comic series. And now I know my opinions on adaptations have definitely shifted, because I think the show is better than its source material. Realizing that it is, in fact, okay to think these thoughts—thoughts that a younger me would have considered bordering on blasphemous—I wanted to reconsider my experience with Practical Magic, and adaptations more generally.

And here is where I notice the first major difference in my experience of Sabrina vs. Practical Magic: order of operations. I read Practical Magic first and saw the movie later, but with Sabrina I experienced the show before going back to read the comics. Perhaps we tend to imprint on our first experience of a story and that may be what determines the nature of our comparisons. True or not, I find that the comics are less interesting than the Netflix show. Like Practical Magic, the show borrows elements of the source material and uses them to very different ends, though I would argue that, in this case, it adds interesting material and fleshes out the characters we meet in the comics (rather than cutting and simplifying, as the movie did). Frankly, I found the comics, written by Roberto Aguirre-Sacasa, a bit of a letdown; they basically just ask “what if Sabrina the Teenage Witch was, you know, dark?” And it is very, VERY dark. The kind of darkness that sacrifices character and story for creepiness and shock value.

The other major difference, obviously, is grounded in the distinct mediums involved. Cutting a novel down to a movie that clocks in under two hours is very different undertaking than spreading an already-thin comics story across ten episodes of television. I’ve always known, logically, that film and books offer fundamentally different experiences and the languages of these mediums are not always compatible. The same goes for comics and TV, or short stories and film, or any combination thereof. Each does something unique with its material, something that doesn’t translate entirely when it is moved to a new format. This theoretical knowledge hasn’t prevented me from completely melting down about the “betrayal” of a lousy adaptation—but when is that reaction fair and when is it just being a fan who is impossible to please?

Buy the Book

Burn the Dark

Stephen King famously hates the Stanley Kubrick version of The Shining. From a creator’s perspective, it’s hard for me to blame him. Kubrick borrows only the barest elements from the novel, alters all the characters to suit his vision, and completely trashes the theme of addiction and recovery that runs so strongly throughout the book. King hated the film so much that he heartily supported a new version (a made-for-TV miniseries) that was more faithful to the source. We all remember Kubrick’s Shining; I don’t think most can say the same for the later, more faithful “correction.” And that’s the conundrum that runs my brain in circles: what can you call a good adaptation? I don’t think it’s very fair to consider films like The Shining to even be an adaptation—its inspired by an idea, perhaps, but it is its own beast. Sometimes you get lucky and the author of the original work writes the screen treatment—and the stars align in some unnamable way—and you get films that are as good (or better) than their sources, like The Princess Bride or Interview with the Vampire or The Shawshank Redemption.

I can’t remember if I was excited when I found out Practical Magic was being adapted into a film. When I did encounter it, I was immediately irritated. It leaned very hard into the witchcraft element and the novel isn’t really about magic or witchcraft as a practice or ideology. Magic, as such, is a bit of an undercurrent to the story, something that may or may not be literally real; Hoffman uses elements of magical realism throughout and you’re never quite sure if the Owens women are witches in a literal sense or if “magic” means something else altogether.

The story centers on orphan sisters Sally and Gillian Owens, beginning with the loss of their parents as children and skipping and jumping across their lives before coming back into focus when the pair are in their mid-to-late 30s. As far as very basic overviews go, the film and the book are on the same page. But whereas the book is mostly focused on the interior thoughts and motivations of the characters, movies (generally) need to focus on a plot, so the death of Gillian’s abusive boyfriend Jimmy is reworked into a plotline about irresponsible magic use and a very on-brand late ‘90s homage to the power of sisterhood.

But if I remove the experience of the book—just mentally set it aside while considering this—does the movie stand on its own just fine? Honestly, yes. It’s a product of its time in a lot of ways, and yet ahead of its time in its focus on the relationships between women, family, and community. One of the major changes from the book to the film was the fleshing out of the aunt characters, played magnificently by Stockard Channing and Diane Wiest, who make the film about a million times better every time they are on screen. The film has different goals than the book—and that might actually be okay.

To hope that a favorite novel or story will come directly to life via moving pictures is something we keep clinging to—but it never really does, not in the way I think many fans desire and demand. Some of the most faithful adaptations are often failures, mostly because of the soullessness that can occur when creators are unable to bring their own vision to the material; attempting to reproduce someone else’s work has got to drain some of the magic out of the whole process, leaving a vacuum. Meanwhile, others make additions, edits, and eliminations that certain hardcore fans hate but that most people accept as necessary, like those made in the Lord of the Rings trilogy or the Harry Potter films (and while they aren’t SFF, I’d add most classic literature adaptations to this pile as well).

And what does it mean when we say that an adaptation is “better” than the original? Is it still an adaptation, or is it something separate and new? The NeverEnding Story comes to mind; better or worse is sort of thrown out the window when the film becomes so beloved by a certain generation that few realize it was based on a book at all. The book’s author, Michael Ende, hated the film version. And then there are cases of notoriously “bad” adaptations like Mary Poppins: Disney gutted P.L. Travers’ original work to create something entirely different, enraging and deeply wounding the author. Yet the film is beloved as a classic, and many fans have forgotten (or never knew) it was an adaptation at all. As in the Stephen King situation, you have to consider: as a viewer, does it matter? In so much that we will likely always be determined to judge an adaptation against its source (and authors will always be rightfully biased in favor of their work), yes, it does. But really, in a practical way? Probably not.

So, has this little comparative exercise taught me anything? Not in a direct way, no. But it did help me to pinpoint and articulate some nebulous ideas I have been toting around in my brain for a while. I think I’ve finally come to accept that expecting an adaptation to completely capture a book may be wishful thinking—even in the era of big-budget prestige television—and that sticking mindlessly to that expectation will cost you a lot of fun. I could have spent years just enjoying Practical Magic for what it was, instead of obsessing over what it wasn’t. (The same can’t be said for Queen of the Damned, which comes from another favorite book; that movie is still really terrible). But I think I’m finally in recovery from the adaptation-purist stage of my life—just in time to put it to the test with Good Omens and the completely off-book Game of Thrones finale around the corner!

What adaptations have you struggled to accept—or simply refuse to? Which ones do you love? And which ones are you looking forward to (or maybe dreading)?

Originally published in April 2019.

Amber Troska is a freelance writer and editor. When she isn’t reading, you can find her re-watching Stranger Things again.

Seems only fair. Anthony Burgess hated Kubrick’s version of A Clockwork Orange.

The first question I ask myself is whether the change was essential because of the differences between print and video. For example, The Hunger Games books include a great deal of internal monologue. That’s impossible to film, so lots of changes have to be made. I’m generally happy to forgive that.

The second question is whether an unnecessary change is nevertheless well done. Examples from GoT might be juxtaposing Arya with Tywin Lannister in S2 (rather than Roose Bolton, as in the books) or the changes made to the scene at the Inn with Polliver in S4. In both cases I was slightly annoyed by the changes, but I also had to admit that the scenes were great on their own.

Then there are scenes added just to do something “cool” on film. An example here might be the silly dragon chase scene from Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire. I hated that scene. It wasn’t in the books, it wasn’t necessary for the story, and it struck me as silly. Add too many scenes of this kind and I really won’t like the movie.

Good timing on this article. With all the discussion around Discworld lately, a discussion about adaptations has been much needed.

It’s tricky, really. For so many of us, it’s exactly what you state – what did we encounter first? How we imprint on that often dictates how we react to further exposure to material in the same family. Readers tend to visualize (in many different ways), and when visual adaptations don’t match our expectations, it can be difficult to accept, at least initially. But some who see the visual presentation first (think of those who were first exposed to Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings, for example) will always have those visual cues in their minds, even when they read the source material which may differ in significant points.

I guess there are two main questions I’ve considered about adaptations, one of them significantly more controversial than the other.

Firstly, how much does it matter whether the characters in the adaptations truly match the characters in the source material? And yes, I’m talking about sex / race / appearance. These markers of identity do carry meaning and so when this is changed in adaptations, does that affect our acceptance or lack thereof? Is it good or bad to have strong feelings when changes are made to characters in these areas? Does it matter?

Secondly, does the adaptation hold true to the soul of the source material, as it were? Do the thematic elements closely map? Does it “feel” right? This is nebulous and not always easy to define and there will be many different opinions. But generally, for me, this is usually what determines if I like an adaptation or not. Does it feel like the author of the adaptation truly understands the source?

These above questions will often determine whether someone enjoys and appreciates the adaptation. But what I have not yet discussed is expectation. Someone who loves the source material will long for an adaptation that hews closely to it. They want to see what they imagined in their heads. They want the same notes that rung true in their hearts as they read the source, to ring true in their heads when they watch the film. When I watched the classic Sense and Sensiblity (of the Rickman / Grant / Thompson / Winslet fame) recently, I had just read the book. And I expected the movie to not be that similar (just a movie, after all – and I have low expectations). I was stunned and delighted to find that whoever made the movie got the book and in my mind, this was a brilliant adaptation, in spite of the cuts they had to make to fit the story to a movie. I laughed and cried at the same moments during the movie as I did during the book. Perfection. Is it wrong to want an adaptation that hews closely to the source material? I would argue not. Another example. A Wrinkle in Time is one of my most beloved books. I would deeply love to see a movie that gave me the story of the book, matching its tone, themes, etc. Have I yet seen one? No, I have not. This saddens me, because I love the book so, and I’d love to see it portrayed on screen in a faithful manner. Maybe I shall see this someday.

So I would argue it’s not wrong for ones to want an adaptation to closely match the source material.

But….it’s also not wrong for someone to make an adaptation that veers off into its own territory and does its own thing. As stated, some of the most brilliant movies out there were adaptations of books that bear little resemblance to source. And the movies sing. If a director/writer has a story to tell, then do it. Just do it beautifully and do it well.

The end of this rambling comment? I suppose just to say that we all have room to both agree and disagree on the subject of adaptations. It’s alright to want an adaptation that is a mirror-image of the source. Why would we not want that? But it’s also alright to enjoy an adaptation that is very much different…if there’s truth and beauty contained therein. We are all creators of art, in our own ways, and I’d rather see more art out in the world, not less. (I’m still hoping for a good adaptation of Wrinkle in Time, mind!)

I used to be a purist as well, but have become more chill as I got older. Two things that still drive me up the wall though are (1) when adapters go on & on about how they are going to be faithful to the source material, then still go & do whatever the frell they want (which is fine, just don’t lie about it!). And (2), when really cool stuff from the source is cut and then really really stupid crap is added for ‘reasons’.

I almost broke up with someone over an adaptation. I love Doc Smith, and I love anime, so the Lensman movie adaptation from Japan (with CGI starships!) was emotionally huge for me. Imagine my let down on seeing it re-worked into a cross between Star Wars and Green Lantern (admittedly a comic which was much inspired by the Lens in the first place). I staggered out of the movie theatre just broken and when my date couldn’t understand why I was upset we had a huge blowout.

Nowadays I understand better the need to adjust elements for an adaptation, but when things drift too far, I can still be angry about the new creators stealing an existing name and goodwill for their own project.

A great example of the conflict you mention, I’m solidly a purist when it come to adaptations. I’m willing to forgive changes that are clearly necessary for length/pacing, such as the omissions from LotR, but not much beyond that. On the other hand, I really enjoyed the Ready Player One adaptation, despite the fact that it followed basically none of the events from the book, which I also loved, because it so perfectly captured the spirit of the book.

I tend to fluctuate between “but they left out a part that was my faaaavorite!” and “eh it’s an adaptation and they needed to make choices.” I think as I’ve gotten older (a theme in the comments, I see), I’ve gotten more chill about an adaptation needing to be a carbon copy of the original work (as if such a thing were possible).

As others have mentioned, I think what’s most important to me is that the tone of the adaptation match the tone of the original. For example, the Lord of the Rings movies were sweeping epics, like the story, so I thought they worked well as an adaptation. The Hobbit movies, meanwhile, attempted to be sweeping epics while the book they were based on was a short children’s tale. I understand why Jackson wanted to make the tones of his movies match, but the source material is VERY different in tone.

Hewing too closely to a book can suck some of the soul out — books and movies are inherently different media, with different strengths. I think the first 2 Harry Potter movies drag a bit for me because they are trying to replicate the books almost exactly instead of making some choices that would make them work better as movies.

hdvane – I’m with you on the Hobbit adaptations!! I remember when they announced that Peter Jackson was going to direct them and most people were getting excited. I remember being distinctly nervous thinking…”Oh no, he’s going to try and mimic the feel of the LotR movies because those were so popular…but that’s not at all the way the Hobbit movie should feel!!” Sadly….I was proved right.

Whilst I appreciate that the article and comments following emphasise a subjective appreciation for the source material, and often a disappointment with the adaptation. My view is somewhat different.

I think it is often budget that is the issue. I see grand armies, fantastic Starships, powered armour and real space cities. But often the budget or ability is not there to deliver.

The look and feel of a world makes all the difference to me. Too many indoor scenes or “outdoor” locations which are clearly in the studio throws me out of the wonder.

I don’t mind minor character changes or squashing a plot for brevity. But, like Good Omens, if the look and feel was sacrificed to the budget and ability to deliver then I feel disappointed.

It is important to recognize that different media tell stories in different ways, and that the adaptations that work the best may be showing us things in ways that are different. Fiction writing is descriptive; filmmaking is demonstrative. Consider a text like “Watchmen”. The movie was very nearly a panel-by-panel remake that left a lot of people disappointed. On the other hand, the recent series worked exceptionally well, and was, I believe, well-regarded by fans. What did it do that was different? One thing was that, like a good comic, it told a new story, in universe. That’s actually something that we are used to in comics. Unlike, say, Spider Man movies Spider Man comics tell new stories every time, without rehashing (much). We expect that, and when we get it we are more likely to be excited by the new thing that is like the thing we liked, but not exactly like it. When a movie adaptation shows us something familiar in a new way that’s enjoyable.

I would say that a good adaptation (as opposed to a good quasi-original work inspired by an existing work) is something that retains the soul of the original while making it more suited for a different medium.

Ang Lee and Emma Thompson’s Sense and Sensibility is a great adaptation. It retains the mood and style of the original work, while making alterations to elements that would not suit modern audiences (gives Edward Ferrars a personality, provides a plausible reason for Marianne to become deathly ill).

In contrast, Peter Jackson’s The Lord of the Rings trilogy frustrates me because it is exceptional in capturing the visuals of the book – the labour and attention to detail that went into sets, costuming, and cinematography is staggering – but misses its soul. It treats Frodo’s mercy towards Gollum as a mistake, and Gollum in ROTK as solely malicious, when in fact Frodo’s mercy is what enables the quest to succeed. I’m happy with the excision of Bombadil and the Barrow-Downs (insufficient time, would disrupt the plot flow), I can live with the insertion of Elves at Helms’ Deep (movie audiences don’t have appendices telling Lorien was at war too; it’s good to communicate that the elves weren’t doing nothing) and the removal of the Scouring of the Shire (the ending of LOTR is very lengthy for cinema even as it is), but I can’t get past the loss of the central theme of the book, that we receive mercy by offering it, even when unmerited.

More thoughts:

Another example of a great adaptation is the stage musical of Les Miserables. The thing that sets it apart from movie or TV show adaptations is the way its nature as a musical allow it to capture the deep internal conflicts at the heart of the novel – Valjean’s repentance in response to the bishop’s grace; Valjean’s conflict over his decision to turn himself in to save Champmathieu; Javert’s thoughts before his suicide. These are key moments, but they’re internal and without dialogue; the musical’s songs (which are brilliant written, and encapsulate the core of Victor Hugo’s lengthy descriptions in the space of a few verses) allow it to bring them out.

It has some slip-ups (in the book, Javert isn’t meaningfully religious beyond deep respect for the church as a institution of respectable society) but it’s an exceptional adaptation that makes the most of its medium.

I tend to prefer adaptions which adapt, rather than attempt to visually record every action and line of dialogue. If the movie or TV show can’t live on its own as a piece of art, then no matter how faithful it was to its source, I think it fails.

That said, while I don’t mind changes to plotlines, characters, or anything else, if the changes indicate a lack of understanding of the source materials’ central theme, I think the adaptation fails as well.

In the second camp I’d put things like the film version of The Golden Compass. I’d also include Return of the King almost solely because of the removal of the Scouring of the Shire. I see that as the last death of Frodo’s innocence, that after this harrowing experience he goes home to find more destruction, not the peace he expected. It’s why I understand in the books why he leaves Middle-Earth, where the film fizzles out thanks to the dragged-out happy ending.

Overall, I think it’s easier to articulate what makes an adaptation fail, than what makes them work…

For me the overall spirit—some combination of look-and-feel along with the narrative tone—is the key aspect for declaring an adaptation “good”. A close second is to be satisfied that any significant deviations from the source text were not gratuitous, but instead requirements of the visual medium.

Most of the discussion here presumes that success or failure of an adaptation is solely the responsibility of the producers/showrunners, but arguably some of it has to fall upon the audience too. Sitting down to watch an adaptation with the thought “I must see X, Y, and Z on the screen” is almost certainly the surest way to be disappointed. A fair-minded viewer should be open to the idea that some element that spoke to them so clearly on the page may not actually be so essential to the story as to require an explicit scene; instead, that element could be an aspect of worldbuilding, character development, etc. that can be introduced in some indirect manner on the screen.

I think the issue becomes interestingly muddled when talking about adaptations of multi-part works because the concept of “source material” gets a bit fuzzy. For example, the final three Harry Potter films are somewhat problematic adaptations of the published novels, but as adaptations of the underlying stories as filtered through the previous films they work just fine.

I’ve seen both and read The Shining and A Clockwork Orange; Kubrick’s changes made them both outstanding movies, but, yes, they were less than faithful adaptations of their sources. Two of the things that reportedly annoyed Burgess about Kubrick and A Clockwork Orange were the omission of the book’s last chapter, which was about Alex’s redemption, and Kubrick’s abandonment of Burgess when the film came under attack for its violence.

I think a different case is Blade Runner, the adaptation of Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?. The movie is so radically different from the book that it’s not really an adaptation; it’s a story sharing a few characters and a vague semblance of the milieu of the book. I happen to like the movie better than the book, but reading the book and seeing the movie wouldn’t give much in the way of spoilers for either.

Faithful adaptations can make weak movies, especially of long, complex novels. Egregious or stupid changes, like in the deservedly reviled adaptations of Wizard of Earthsea (probably one of the worst cases of whitewashing characters) and the commercial adaptation of Lathe of Heaven (the PBS one was better), the movie U-505 (which replaced, among other things, the navy that actually captured the submarine with the USN) cause their own variety of bad.

I also had given up hope that “good” or faithfull adaptations could be done. And that was after Harry Potter which overall is relatively good.

But when the first 3 seasons of GoT came out, I regained hope. I want all my favorite series to be adapted like those first GoT seasons. And it didn’t only work for the book readers, obviously it also worked for show only fans.

The Show even added scenes that are good additions (pairing Arya with Tywin).

That isn’t to say that unfaithful adaptions can’t be good. The attempt to be somewhat faithfull can even backfire (e.g. “Avatar the last airbender”), and make the movie enjoyable for nobody. But if it’s not trying to atleast somewhat appeal to the themes of the original, I would rather they don’t make it at all. At that point you are just abusing the name recognition to sell something barely related.

I don’t feel that adaptations have to slavishly follow their source material to be good. Look at The Magicians, which has occasionally pulled plots or themes from the books, but has generally just used them as a style guide for making their own stories.

That said, even relatively close adaptations, like The Expanse can make changes for the better. In the case of the Expanse, they make a point of introducing characters (eg Bobbie, Avasarala), earlier than they were introduced in the books, to give us a chance to get to know them before they become pivotal in the plot. This is partly because TV/film makes it slightly easier to skip between different characters (as long as they and their surrounds are somewhat visually distinct), in a way that would be confusing in print. ie, they’re playing to the strength’s of the medium.

Just in time to watch the rest of GoT eh? oh man……

I’m sorry I can’t address everyone individually, but I just want to say how happy it makes me that my little personal meditation on adapting books is bringing people out to give such lovely and thoughtful comments.

For me, there’s one very important rule that adaptations cannot break: do not assume the audience has read the source material! Otherwise, you wind up with a nonsensical mess. A good example for me is the recent Witcher series. I couldn’t really enjoy it as I was thoroughly confused at what was happening. I felt the show made no attempt to explain itself as a completely separate entity from the books.

The Harry Potter movies make no sense, either. I was a huge fan of the books—going to midnight releases and debating endlessly online—but viewing the movies from the perspective of someone who didn’t read the books, it just didn’t make sense. The powers involved clearly assumed most of the audience was familiar with the source material, so they just did whatever seemed cool. The whole background about the Marauders in the Prisoner of Azkaban? Don’t need it! Never mind that it’s plot relevant and the exclusion from the movie makes the plot nonsensical…

It’s definitely a tricky tightrope to walk, both as creator and enthusiast (I tend to dislike the term ‘fan’ anymore as certain circles have made it more of a perjorative in my mind than a compliment). I think the order in which you take in the works makes a difference.

Case in point, Netflix’s adaptation of Altered Carbon. That book had long been on my “I should get around to reading that” so I was naturally drawn to the series. My friend Dianna had been the one recommending the books. So I ended up watching Altered Carbon, and then reading the three book series afterwards.

My take on the adaptation was that it was alright. I enjoyed it, and I thought it did alright by the source material. Dianna had the opposite take. In her view it made some truly egregious flaws and for that it fell far short of the mark. To be honest, I could see her point, but also in my mind I was playing the “how would I do it?” game, and I mostly understood the choices the scriptwriters made. Certain book elements certainly weren’t perfect, either introduced with not enough foreshadowing, and the cast of characters needed pruning down to make scenes tighter for stage production. And yet, at least one character relationship choice will need delicate handling in the future if the series is to continue because of these choices and I could see it deviating from the source far more depending on how nuanced that is handled.

I tend to chalk this up to the fact that I saw the story before I read the story. When we read, we are the gods of our own imaginations. There’s no limit to the sets, a character pantheon can be as large as needed and remembered. We infuse characterizations not only with the author’s intent, but our own context we bring to the story. Viewing a story is a wholly different experience where there’s a budget, we are told exactly without variation how this character appears, how this character behaves, what this character believes (though as an aside a truly deft script and nuanced acting gives as much leeway to the latter aspects of this — witness the Good Omens adaptation and the really amazing chemistry between Sheen’s Aziraphale, and Tennant’s Crowley). Dianna had read Altered Carbon and the books before, had digested them, made them a part of herself, and thus any representation that’s streamlined with a budget is naturally going to fall down.

Another adaptation that I haven’t been able to make up my mind about is The Magicians. I read the first novel quite awhile ago — didn’t care for it to be honest. Saw the first season of the show, though it was fun. Went back to read the novel and the sequels which really completed the character arcs that I found problematic in the first. Went back to the show and I still enjoy it though it is radically different. And now I’m working on a reread of the three and what I’m getting is a blend of the two in my mind and that’s not a bad thing. In particular Rick Worthy who plays Dean Fogg has completely overtaken the book character and is far superior to the pseudo-Dumbledore that’s portrayed. That actor isn’t the only one who I’ve willingly supplanted in my head canon but probably the most standout one. At the same time, the book is tighter plotted, and the various characters arcs of maturation are more satisfying (and of course do not need to adhere to schedules or budgets). And at the same time, the show is fun because it’s interesting to see how it draws upon the source material, blending storylines, making new ones up, and putting the characters through them.

And as far as I try to be with the above works… I’m deeply worried about The Watch as an adaptation because while as I have said, I try to be fair, I really think this one might be a bridge too far. However again, I’ve read Pratchett’s work first, and have invested deeply into the characters, the world, and the literature. So I may not be the most fair judge, but I’ll do my best.

To my mind the key element of any Good adaptation is fidelity to the Spirit of the original, even if elements of the form are altered and adapted to fit a very different medium; put simply I am willing to accept changes to the events of a story, provided that the new version is loyal to the characters of the original (both the individual character of the work itself and the cast of Dramatis Personae that help make it interesting).

In a nutshell I feel that what defines a Good adaptation is the impression that intelligent changes have been made to tell the original story in a new way (for a new medium or a new generation), rather than the feeling that old names have been exploited to sell an entirely different story (I was tempted to write ‘new story’ in place of ‘different’ but one cannot claim to be entirely against cinematic sequels to literary originals on principle, though in practice this can certainly be objectionable).

Summed up – a Good adaptation can be a simplification or an elaboration, an ‘Alternate History’ or an outright sequel, but it must NEVER be a distortion.

Questions I ask when evaluating an adaptation:

Did they correctly determine which aspects of the original work could be feasibly retained in the new medium, and which are not feasible?

If the non-feasible elements were a major part of the work’s themes, how were they replaced?

Did the adaptationist understand the themes and motifs of the original and recreate them within the idiom of the new medium?

For what it’s worth, I considered the first LotR movie to be a good adaptation, and the latter two to be bad.

@6&7, Tolkien himself revised the Hobbit some after the success of the LotR to bring it a bit more in line, at least with background. And I think much of the problem with Jackson’s adaptation of it was that he was thrust into it at the last minute. He didn’t have the same amount of time in pre-production that he had with LotR, and used CGI to fill in some of the detail. I quite enjoyed them, but nowhere near as much as I loved LotR.

I think there’s also a need for movie makers to be more specific about how close a movie will be. There’s a difference between “inspired by”, “based on”, and “adapted from”. The first says to me that the work is something different than the source, the second says it is closer to the source, and the third should be for very close creations. So when a director says it is an adaptation of a work, but clearly is only loosely connected, the director really should be saying it is inspired by the source.

@23 BonHed

Oh man, when I heard there was going to be a TV adaptation of Lucifer I was stoked. I really enjoyed Mike Carey’s work on the comic. The TV show is so different that if it weren’t for Mazikeen and the night club I wouldn’t have any idea it was “inspired by” the comics at all!

All indications are that it’s a decent show in its own right though (and how can you go wrong casting Tricia Helfer as his mother…)

@24 I didn’t believe it even after I saw the comics in the credits several times. I was always like: wait, what?

This article was perfect, and interestingly enough, I recently read Practical Magic after adoring the movie, and we left saying eh. The book was not as good to me as the movie was – I think it may be timing. That the book wasn’t something I needed at the time I read it, and the movie so very was.

In a related note, I also recently TRIED to read Forest Gump and could not get through it. I thought the writing was terrible, and it was just NOT my kind of book – however the movie is touching and beautiful.

I think sometimes we need to just let go, and accept that the book and the movie are often NOT the same, and that it is okay to like one over the other, or like them both for their own sake (as I feel about all the versions of The Shining).

I liked Stardust the movie more than Stardust the novel. They have some characters in common, but you can see that Neil Gaiman and the movie producers wanted to tell different stories, and they both work (I just like the movie more, it’s more fun).

There are certain scenes and character moments that resonate with readers of books that to me are essential to capturing the spirit of the story, and if those are removed or altered too much it really hurts an adaptation for me. Faramir’s behavior in the LOTR adaptation, for instance, was the opposite of how he behaved in the book and was such a disappointment. Eowyn however was spot on, and Jackson’s additions to her character were wonderful. Overall he did a good job so I forgive him for Faramir. Other adaptations are not so good.

The first one I think of is always The Dark is Rising. It’s unrecognizable, in character and story and themes. It’s like it was written on Opposite’s Day. The only thing the two stories have in common is that the Dark Rider rode a black horse. I have no idea what the adapter was thinking, maybe that he was a better storyteller than Susan Cooper, but I hope he never touches another children’s novel again.

I do tend to prefer whichever version I see or read first, because that’s usually the one I fell in love with. But I’m happy to see that view stretched so long as it feels like the writer and director “got” the story they’re telling. I’ll throw in two children’s novel adaptations I love, The Black Stallion and Howl’s Moving Castle. They’re not the same by any means, but they’re wonderful.